One White Pine: Building Spaces for Living & Healing

Professor and landscape architect Daniel Winterbottom has been designing and building therapeutic gardens for over 20 years. Here, he shares his unique viewpoint on the power of nature to heal communities and individuals facing medical treatments, PTSD, and violence.

How did you personally come to see the power of natural environments?

My dad is from Canada and their idea of a vacation was camping. We'd all be packed into a car, slip off to Vermont or Maine or somewhere and set up the tent. I had some challenges, I guess you could say, as a kid. It became very much a therapy to get away from addictions and challenges like that.

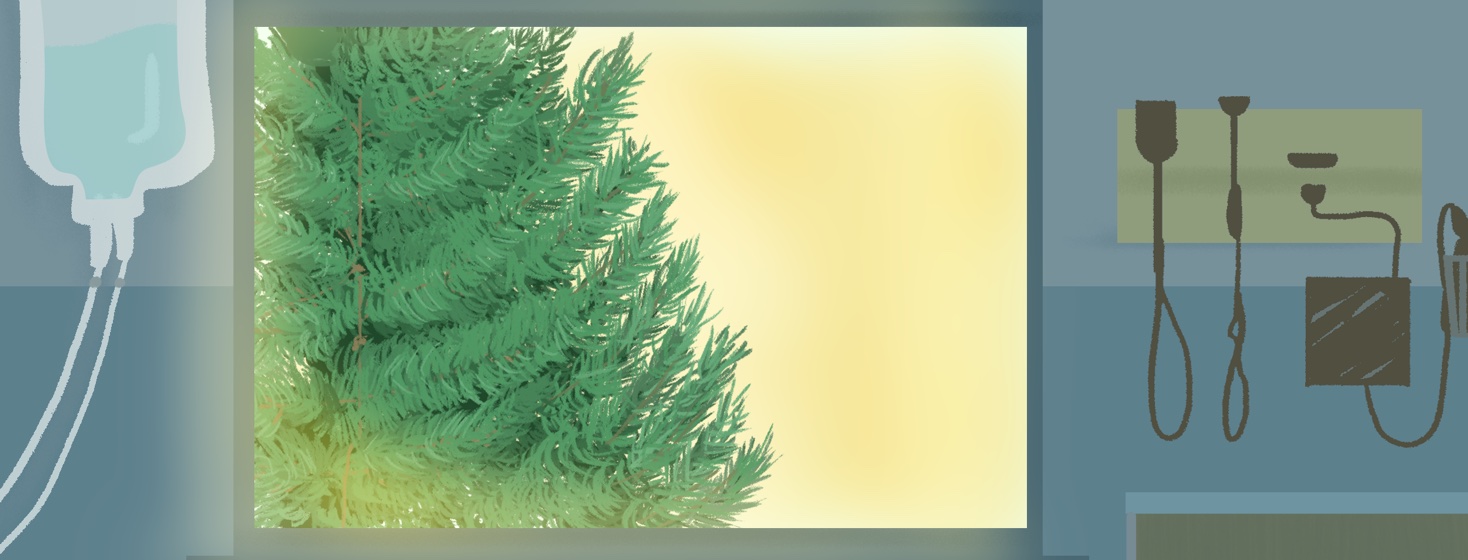

My mother was diagnosed with ovarian cancer. I was 36. I went through it with her at the hospital. I was struck by how focused she was on nature. There was one white pine tree and she would talk incessantly about that tree. When we came home we would spend enormous amounts of time in our small garden and driving through Jersey. That stuck in my mind.

How did you become involved in landscape architecture?

I didn't get into landscape architecture until relatively late. I dropped out of school for many years and finished undergrad late. My training was in fine art in the ‘70s. I went as a painter and became a sculptor, then a sort of more land/environmental artist.

My wife said, “There’s this profession and school across the river,” which was actually Harvard! Landscape architecture combined the art component with social impact, the environment, and construction. At the time I was never thinking I'd ever get into Harvard. And then you open the envelope and it's, “Oh my God, how did this happen?” It's kind of funny to look back and think, man, I was clueless as to where all that was going. In the end, it's something I love.

What is the impact of natural environments on health, and what is its future?

At Texas A&M, Walter Ulrich did a study where half of the hospital patients had a view of a brick wall and half of them had a view of trees. Those who had a view of trees spent one less day in the hospital. They took fewer medications, they had fewer post-surgical complications.1 That simple difference has some powerful effects.

In a study in Finland, they found that being in nature for as little as 20 minutes, even 15 minutes at times, can reduce stress levels.2 Some researchers at California State found that students who go for a walk before a test actually test better than students who have been studying all the way up until the test.3 There are whole movements now for nature prescriptions. In Japan, they have forest bathing.

We can now do virtual nature and it's even being used in solitary confinement in Washington State. I was just at the airport in Warsaw and they had a huge screen showing scenes of the ocean in a stressful environment. But does this mean that people are more willing to sacrifice nature and become less active environmentalists because they can simply have it on the screen?

What does your work look like? What are your favorite projects?

My students and I at the University of Washington work around the world. Most of that work is focused on bringing natural environments to those with a critical need for it. This could be VA hospitals, cancer facilities, psychiatric hospitals, prisons, etc. I've worked in all of those.

We worked in Guatemala with families who live and work in the garbage dump. Many of them were single mothers trying to raise a family in dire poverty. It was a place that was completely devoid of nature. Any trees were cut down for firewood. The gangs ran the entire neighborhood. Kids couldn't go out after certain hours.

And here was this little patch of nature that created a safe zone for these kids. The idea was that, despite poverty and violence, they would have some semblance of childhood and maybe that would put them on a different track.

Cancer Lifeline was started by a woman that passed away from breast cancer. She established a community for people who were very isolated. Many of them came from Section Eight housing and didn't have family support. They weren’t well connected to the hospital system.

An amazing art therapist invited us to do gardens upstairs. The Garden of Play, the Garden of Discovery, and the Garden of Contemplation. People could go and meditate or socialize or celebrate. One of them was used by staff because there was a lot of burnout. The other two complemented a whole curriculum of physical health, nutrition, yoga, and education.

How can people make their homes healthier environments?

Well, there is quite a bit of research looking at houseplants, so I don't think you have to have a yard necessarily. I mean, you can do small interventions: balconies, flower pots, terrariums, things like that. People also talk about hearing nature sounds like using chimes with bamboo.

There's a whole body of research that looks at plants in the workplace, largely potted plants. They have been shown to be very good for refocusing energy.

Animals are also considered to have a very positive effect on many people. I've seen enormous transformations with service dogs.

I don't think it has to be Versailles or anything. It can be quite small and minimal. Japan is an example. You'll see small houses with small viewing gardens. They could be four feet by four feet. And of course, they do miniature things that represent a greater landscape. So they've been practicing this for, you know, thousands of years. You can integrate nature into the most modest of spaces with the most modest of means.

Join the conversation