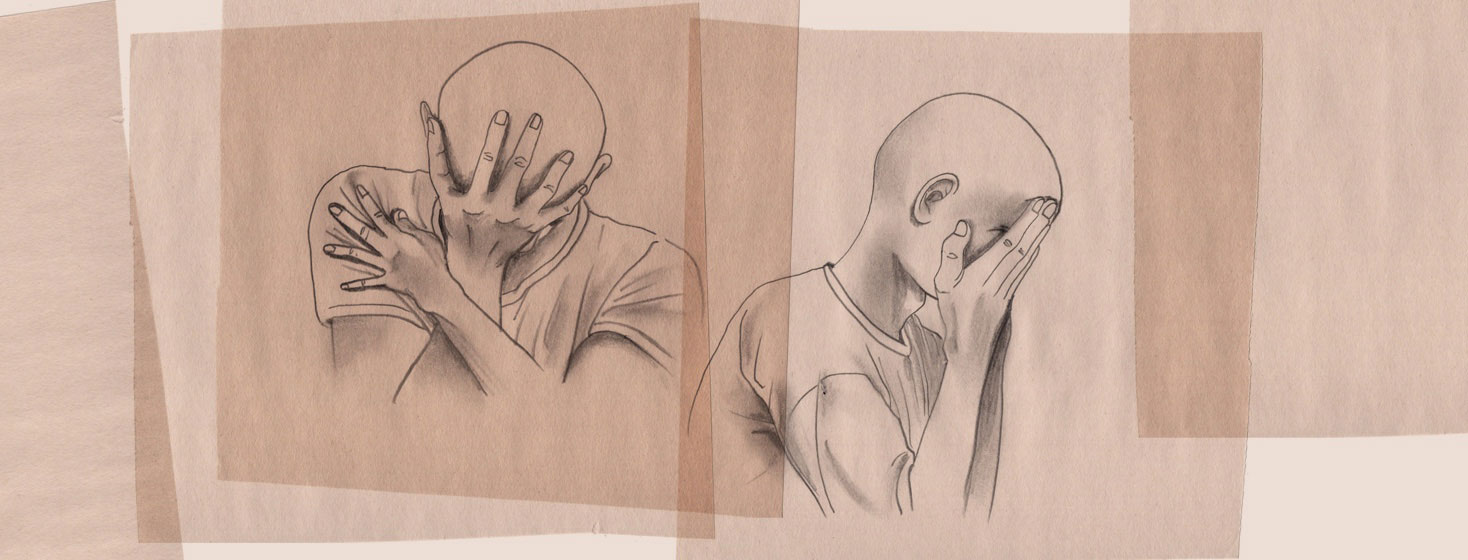

Shame: The Other Silent Killer

My father first found out that he had hepatitis C over 25 years ago during a routine screening. He was of the Baby Boomer generation and was the target of the mass push for everyone born between 1945 and 1965 to be tested. After it was explained to him by his physician how someone could contract hepatitis C, my father was faced with a hard reality of the consequences of his many years of substance abuse. He confided in me that he had probably contracted it in the early 80s when he last shared a needle with someone who he later found out was also infected.

My father struggled with substance

Unfortunately, my father’s substance abuse issues were not a thing of the past. Even though he was no longer using IV drugs, he was still dependent on Percocet and Valium at the time of his diagnosis and was getting them prescribed by an Orthopaedic Surgeon for “nerve damage” from exaggerated injuries from car accidents and slip and falls. He was definitely not in a place to admit that he had a problem. He knew that to begin the process of getting treated for his hepatitis C meant that he would not only have to face his past, but that he would also have to confess his ongoing use, and risk having his precious pills taken away from him. And so, for the next two decades, my father continued to go about his life, making up various excuses along the way whenever me or my mother would encourage him to seek treatment.

Like many people, he felt ashamed

I knew my father was full of shame and this knowledge of his shame wasn’t just coming from my own understanding of shame’s place in active addiction vis a vis my training as a Psychotherapist – he had directly engaged me in candid discussions about how ashamed he felt about a lifetime of poor decisions and how they had landed him in his current dwelling of utter desolation.

In 2017, less than two years after my mother died due to secondary causes from her own addiction, my father finally sought treatment. It ultimately took an entire afternoon of me begging him to not let me needlessly lose another parent for him to finally meet with a hepatologist.

Any fears that he had about his pills being taken from him were unfounded – no one scrutinized his list of prescribed controlled substances. He was able to proceed with treatment with one condition from him: his Harvoni prescription could not be filled through his regular pharmacy. Instead, the Harvoni was discretely shipped to him through the mail. It was a neurotically clever scheme negotiated between him and his inner addict to maintain the divide between his two new disparate realities.

Treatment came too late

Unfortunately, despite the Harvoni’s success in curing my father’s hepatitis C, it was too late. The decades of quiet, festering shame had instigated their own viral destruction and he was diagnosed with late stage, incurable liver cancer just 8 months after his cure.

Join the conversation